Regex

This is my attempt to document all my knowledge about regex. I will keep updating this whenever I learn something new about regex.

I. Introduction:

1. What is a Regex?

A regex is a text string that describes a pattern that a regex engine uses in order to find text (or positions) in a body of text, typically for the purposes of validating, finding, replacing or splitting.

2. Several ways of doing the same thing

^(?=(?!(.)\1)([^\DO:105-93+30])(?-1)(?<!\d(?<=(?![5-90-3])\d))).[^\WHY?]$

II. Is a Regex the Same as a Regular Expression?

A regular expression referred to what the mathematician Stephen Kleene described as a regular language, which itself referred to a mathematical property called regularity. Regular expression engines that conformed to this regularity were called Deterministic Finite Automatons (DFAs). The name of the father of regular expressions (Stephen Kleene) is immortalized in the Kleene star, the small character in A* that tells the engine that the character A must be matched zero or more times.

In the 1980s, programmers could not resist the urge to expand the existing regular expression syntax to make its patterns even more useful—most notably Henry Spencer with his regex library, then Larry Wall with the Perl language, which used then expanded Spencer’s library. The engines that process this expanded regular expression syntax were no longer DFAs—they are called Non-Deterministic Finite Automatons (NFAs). At that stage, regex patterns could no longer said to be regular in the mathematical sense.

III. Quick-Start: Regex Cheat Sheet

Regex is holder for text. One letter in regex can hold 0 to ∞ letters in matching language.

IV. The Many Uses of Regex

Helps in validation and searching. Simple example email:

(?i)\b[A-Z0-9._%+-]+@(?:[A-Z0-9-]+\.)+[A-Z]{2,6}\b

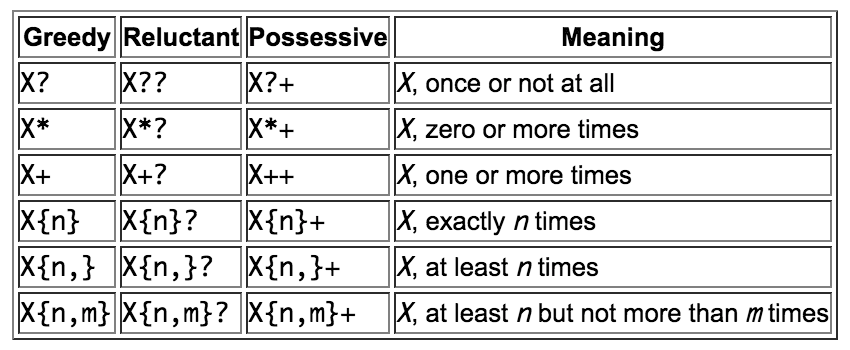

V Greedy v/s Reluctant v/s Possessive Quantifiers v/s Atomic Groups

- Greedy quantifiers are considered “greedy” because they force the matcher to read in, or eat, the entire input string prior to attempting the first match. If the first match attempt (the entire input string) fails, the matcher backs off the input string by one character and tries again, repeating the process until a match is found or there are no more characters left to back off from. Depending on the quantifier used in the expression, the last thing it will try matching against is 1 or 0 characters.

- The reluctant quantifiers, however, take the opposite approach: They start at the beginning of the input string, then reluctantly eat one character at a time looking for a match. The last thing they try is the entire input string.

- The possessive quantifiers always eat the entire input string, trying once (and only once) for a match. Unlike the greedy quantifiers, possessive quantifiers never back off, even if doing so would allow the overall match to succeed.

- An atomic group is a group that, when the regex engine exits from it, automatically throws away all backtracking positions remembered by any tokens inside the group. An example will make the behavior of atomic groups clear. The regular expression

a(bc|b)c(capturing group) matchesabccandabc. The regexa(?>bc|b)c(atomic group) matchesabccbut notabc. When applied toabc, both regexes will matchatoa,bctobc, and thencwill fail to match at the end of the string. Here their paths diverge. The regex with the capturing group has remembered a backtracking position for the alternation. The group will give up its match,bthen matchesbandcmatchesc. Match found!. The regex with the atomic group, however, exited from an atomic group afterbcwas matched. At that point, all backtracking positions for tokens inside the group are discarded. In this example, the alternation’s option to trybat the second position in the string is discarded. As a result, whencfails, the regex engine has no alternatives left to try. Example:

Enter your regex: .*foo // greedy quantifier

Enter input string to search: xfooxxxxxxfoo

I found the text "xfooxxxxxxfoo" starting at index 0 and ending at index 13.

Enter your regex: .*?foo // reluctant quantifier

Enter input string to search: xfooxxxxxxfoo

I found the text "xfoo" starting at index 0 and ending at index 4.

I found the text "xxxxxxfoo" starting at index 4 and ending at index 13.

Enter your regex: .*+foo // possessive quantifier

Enter input string to search: xfooxxxxxxfoo

No match found.

V. The Elements of Good Regex Style

Ask following questions while writing the regex:

1. Should I Capture it or Should I Match it?

You’ll see a diverse use of matching and capturing. Sometimes, the match returns exactly the data we want. But often, the match is a “throwaway” that just gets us down the string, down to the portions we really care about, which we then capture. Sometimes, then, the captured groups contain the data we’re after. But at other times, you only use groups (and back references) to build an intricate expression that adds up to the overall match you’re looking for. What you need to know is: >The Match is Just Another Capture Group

Basically, you can imagine that there is a set of parentheses around your entire regex. These parentheses are just implied. They capture Group 0, which by convention we call “the match”. Likewise, in regex replace operations, \1, \2, \3 (or $1, $2, $3, depending on the flavor) usually refer to capture groups 1, 2 and 3. Not by coincidence, \0 ($0) usually refer to the overall match.

The only moderation I would add to the advice to “use whatever means you need” is that it’s generally considered poor programming practice to spawn unnecessary capture groups, as they create overhead. So if you need parentheses in order to evaluate an expression but don’t need to capture the data, make it a non-capturing group by using the (?: … ) syntax.

2. Should I Split, or should I Match All?

Matching All and Splitting are two sides of the same coin.

Consider a list of fruits separated the word “and”: apple and banana and orange and pear and cherry. You are interested in obtaining an array with all the names of fruits. To do so, you could match all the words that are not and (something like \b(?!and)\S+ would do). Another approach would be to split the string using the delimiter “ and “. Both approaches would provide you with the same array.

This is a simple example, but often you will gain considerable advantage by deciding to match rather than to split, or vice-versa. You’ll often find that one way is easy and the other nearly impossible. Therefore, if someone tells you “I want to match all the…” or “I am trying to split by…”, try not to rush down the first alley because they said “split” or “match”: remember the other side of the coin.

3. Whenever Possible, Anchor.

Anchors, such as the caret ^ for the beginning of a line and the dollar sign $ for the end of a line often provide the needed clue that ensures the engine finds a match in the right place. For instance, when we validate a string, they ensure that the engine matches the whole string, rather than a substring embedded in the string being examined. And anchors often save the engine a lot of backtracking. Be aware that anchors are not limited to ^ and $. Most engines have other useful built-in anchors, such as \A and \G.

4. When You Know what You Want, Say It. When You Know what You Don’t Want, Say It Too!

When you feed your regex engine a lot of .* “dot-star soup”, the engine can waste a lot of energy running down the string then backtracking.

5. Contrast is Beautiful—Use It.

When you can, use consecutive tokens that are mutually exclusive in order to create contrast. This reduces backtracking and the need for boundaries in the broad sense of the term, in which I include lookarounds. For instance, let’s say you’re trying to validate strings that contain exactly three digits located at the end, as in ABC123. Something like ^.+\d{3}$ would not work, because . and \d are not mutually exclusive—this regex would match ABC123456. You may think to add a negative lookbehind: ^.+(?<!\d)\d{3}$. But if you use tokens that are mutually exclusive in the first place, you no longer need a lookaround: ^\D+\d{3}$ works straight out of the box. With time, you come to relish the beautiful contrast between \D and \d, between [^a-z] and [a-z]. This is a variation on When you know what you want, say it.

6. Want to Be Lazy? Think Twice.

Let’s say you want to match all the characters between a set of curly braces. At first you might think of {.*?} because the lazy quantifier ensures you don’t overshoot the closing brace. However, a lazy quantifier has a cost: at each step inside the braces, the engine tries the lazy option first (match no character), then tries to match the next token (the closing brace), then has to backtrack. Therefore, the lazy quantifier causes backtracking at each step. This is more efficient: {[^}]*}. This is a variation on Use Contrast and When you know what you want, say it.

7. A Time for Greed, a Time for Laziness.

A reluctant (lazy) quantifier can make you feel safe in the knowing that you won’t eat more characters than needed and overshoot your match, but since lazy quantifiers cause backtracking at each step, using them can feel like bumping on a country road when you could be rolling down the highway. Likewise, a greedy quantifier may shoot down the string then backtrack all the way back when all you needed was a few nudges with a lazy quantifier.

8. On the Edges: Really Need Boundaries or Delimiters? Use Them—or Make Your Own!

Most regex engines provide the \b boundary, and sometimes others, which can be useful to inspect an edge of a substring. Depending on the engine, other boundaries may be available, but why stop there? In the right context, I believe in DIY boundaries. For instance, using lookarounds, you can make a boundary to check for changes from upper- to lower-case, which can be useful to split a CamelCase string: (?<=[a-z])(?=[A-Z]). However, do not overuse boundaries, because good contrast often make them redundant

9. Don’t Give Up what You Can Possess.

Atomic groups (?> … ) and the closely-related possessive quantifiers can save you a lot of backtracking. Structured data often gives you chances to incorporate those in your expressions.

10. Design to Fail.

As Shakespeare famously wrote, >Any fool can write a regex that matches what it’s meant to find. It takes genius to write a regex that knows early that its mission will fail.

Take (?=.*fleas).*. It does a reasonable job of matching lines that contain fleas. But what of lines that don’t have fleas? At the very start of the string, the engine looks all the way down the line. The lookahead fails, the regex engine moves to the second position in the string, and once again looks for fleas all the way down the line. At each position in the string, the engine repeats the lookahead, so that the pattern takes a long time to fail… In comparison, consider ^(?=.*fleas).*. The only difference is the caret anchor. It doesn’t look like a big deal, but once the engine fails to find fleas at the start of the string, it stops because the lookahead is anchored at the start. This pattern is designed for failure, and it is much more efficient—O(N) vs. O(N2) for the first.

11. Trust the Dot-Star to Get You to the End of the Line

With all the admonishments against the dot-star, here is one of many cases where it can be useful. In a string such as @ABC @DEF, suppose you wish to match the last token that starts with @, but only if there is more than one token. If you simply wanted the last, you could use an anchor: @[A-Z]+$… but that will match the token even if it is the only one in the string. You might think to use a lookahead: @[A-Z].\K@[A-Z]+(?!.@[A-Z]). However, there is no need because the greedy .* already guarantees you that you are getting the last token! The dot-star matches all the way to the end of the line then backtracks, but only as far as needed: You can therefore simplify this to @[A-Z].*\K@[A-Z]+ Trust the dot-star to take you to the end of the line!

VI Reducing (? … ) Syntax Confusion

Confusing Couples

(?: … )and(?= … ):(?: … )contains a non-capturing group, while(?= … )is a lookahead.(?<= … )and(?> … ):(?<= … )is a lookbehind, so(?> … )must be a lookahead, right? Not so.(?> … )contains an atomic group. The actual lookahead marker is(?= … ).(?(1) … )and(?1): The first is a conditional expression that tests whether Group 1 has been captured. The second is a subroutine call that matches the sub-pattern contained within the capturing parentheses of Group 1.

Lookarounds: (?<= … ) and (?= … ), (?<! … ) and (?! … )

A lookahead or a lookbehind does not “consume” any characters on the string. Java accepts quantifiers within lookbehind, as long as the length of the matching strings falls within a pre-determined range. For instance, (?<=cats?) is valid because it can only match strings of three or four characters. Likewise, (?<=A{1,10}) is valid.

Non-Capturing Groups: (?: … )

Within a non-capturing group, you can still use capture groups. For instance, (?:Bob says: (\w+)) would match Bob says: Go and capture Go in Group 1. Likewise, you can capture the content of a non-capturing group by surrounding it with parentheses. For instance, ((?:Bob|Chloe)\d\d) would capture Chloe44.

On all engines that support inline modifiers such as (?i), except Python, you can blend the the non-capture group syntax with mode modifiers. Here are some examples:

1. (?i:Bob|Chloe) This non-capturing group is case-insensitive.

2. (?ism:^BEGIN.*?END) This non-capturing group matches everything between “begin” and “end” (case-insensitive), allowing such content to span multiple lines (the s modifier), starting at the beginning of any line (the m modifier allows the ^ anchor to match the beginning of any line).

3. (?i-sm:^BEGIN.*?END) As above, but turns off the s and m modifiers.

Atomic Groups: (?> … )

When a series of characters only makes sense as a block, using an atomic group can prevent needless backtracking.

- With Alternation

(?>A|.B)C: This will fail againstABC, whereas(?:A|.B)Cwould have succeeded. After matching theAin the atomic group, the engine tries to match theCbut fails. Because it is atomic, it is unable to try the.Bpart of the alternation, which would also succeed, and allow the final tokenCto match. - With Quantifier

(?>A+)[A-Z]C: This will fail againstAAC, whereas(?:A+)[A-Z]Cwould have succeeded. After matching theAAin the atomic group, the engine tries to match the[A-Z], succeeds by matching theC, then tries to match the tokenCbut fails as the end of the string has been reached. Because the group is atomic, it is unable to give up the secondA, which would allow the rest of the pattern to match.

When an atomic group only contains a token with a quantifier, an alternate syntax (in engines that support it) is a possessive quantifier, where a + is added to the quantifier. For instance:

1. (?>A+) is equivalent to A++

2. (?>A*) is equivalent to A*+

3. (?>A?) is equivalent to A?+

4. (?>A{…,…}) is equivalent to A{…,…}+

Atomic groups are non-capturing, though as with other non-capturing groups, you can place the group inside another set of parentheses to capture the group’s entire match; and you can place parentheses inside the atomic group to capture a section of the match.

Named Capture: (?<foo> … ), (?P<foo> … ) and (?P=foo)

When you cut and paste a piece of a pattern, Group 3 can suddenly become Group 1. That’s a problem if you were using a back-reference \3 or replacement $3.

To create a back-reference to the intpart group in the pattern, depending on the engine, you’ll use \k<intpart> or (?P=intpart). To insert the named group in a replacement string, depending on the engine, you’ll either use ${intpart}, \g<intpart>, $+{intpart} or the group number \1.

Inline Modifiers: (?isx-m):

If a modifier appears at the head of the pattern, it modifies the matching mode for the whole pattern—unless it is later turned off. But (except in Python) a modifier can appear in mid-pattern, in which case in only affects the portion of the pattern that follows.

Modifiers can be combined: for instance, (?ix) turns on both case-insensitive and free-spacing mode. (?ix-s) does the same, but also turns off single-line (a.k.a DOTALL) mode.

Subroutines: (?1) and (?&foo)

As you well know by now, when you create a capture group such as (\d+), you can then create a back-reference to that group—for instance \1 for Group 1—to match the very characters that were captured by the group. For instance, (\w+) \1 matches Hey Hey.

In Perl, PCRE (C, PHP, R …) and Ruby 1.9+, you can also repeat the actual pattern defined by a capture Group. In Perl and PCRE, the syntax to repeat the pattern of Group 1 is (?1) (in Ruby 2+, it is \g<1>). For instance, (\w+) (?1) will match Hey Ho.

One can have relative subroutines, named subroutines and pre-defined subroutines.

Subroutines and Recursion: If you place a subroutine such as (?1) within the very capture group to which it refers—Group 1 in this case—then you have a recursive expression. For instance, the regex ^(A(?1)?Z)$ contains a recursive sub-pattern, because the call (?1) to subroutine 1 is embedded in the parentheses that define Group 1. If you try to trace the matching path of this regex in your mind, you will see that it matches strings like AAAZZZ, strings which start with any number of letters A and end with letters Z that perfectly balance the As. After you open the parenthesis, the A matches an A… then the optional (?1)? opens another parenthesis and tries to match an A… and so on.

Recursive Expressions: (?R)

A recursive pattern allows you to repeat an expression within itself any number of times. This is quite handy to match patterns where some tokens on the left must be balanced by some tokens on the right.

To repeat the entire pattern, the syntax in Perl and PCRE is (?R). In Ruby, it is \g<0>.

For instance, A(?R)?Z matches strings or substrings such as AAAZZZ.

Conditionals: (?(A)B) and (?(A)B|C)

In (?(A)B), condition A is evaluated. If it is true, the engine must match pattern B. In the full form (?(A)B|C), when condition A is not true, the engine must match pattern C. Conditionals therefore allow you to inject some if(…) then {…} else {…} logic into your patterns.

Typically, condition A will be that a given capture group has been set. For instance, (?(1)}) says: If capture Group 1 has been set, match a closing curly brace. This would be useful in ^({)?\d+(?(1)})$. Likewise, (?(foo)…) checks if the capture group named foo has been set. Let’s expand this example to use the “else” part of the syntax: ^(?:({)|")\d+(?(1)}|")$.

Lookaround in Conditions: In (?(A)B), the condition you’ll most frequently see is a check as to whether a capture group has been set. In .NET, PCRE and Perl (but not Python and Ruby), you can also use lookarounds: \b(?(?<=5D:)\d{5}|\d{10})\b. If the prefix 5D: can be found, the pattern will match five digits. Otherwise, it will match ten digits. Needless to say, that is not the only way to perform this task.

One can also check relative capture group, recursion level using this.

Branch Reset: (?| … )

It has to deal with the numbering of captured group.

Inline Comments: (?# … )

By now you must be familiar with the free-spacing mode, which makes it possible to unroll long regexes and comment them out, as in the many code boxes on this site.

What if you only want to insert a single comment without turning on free-spacing mode for the entire pattern? In Perl, PCRE (and therefore C, PHP, R…), Python and Ruby, you can write an inline comment with this syntax: (?# … ). For instance, in: (?# the year)\d{4}. \d{4} matches four digits, while (?# the year) tells you what we are trying to match.