Microservices Introduction

I saw this huge post on MicroService Architecture written by Martin Fowler. Though I am very bad at reading but as this post is from Martin Fowler, I know it will be worth the time I will spend on it.

Introduction

Microservice Architecture: suites of independently deployable services. There are certain common characteristics of this approach: automated deployment, intelligence in the endpoints, and decentralized control of languages and data.

In short, the microservice architectural style is an approach to developing a single application as a suite of small services, each running in its own process and communicating with lightweight mechanisms, often an HTTP resource API. These services are built around business capabilities and independently deployable by fully automated deployment machinery. There is a bare minimum of centralized management of these services, which may be written in different programming languages and use different data storage technologies. Also differnt services can scale differently. To understand it in more better way we have to look at the opposite of this approach.

The Monolithic Style:

A monolithic application built as a single unit. Enterprise Applications are often built in three main parts: a client-side user interface, a database and a server-side application. This server-side application is a monolith - a single logical executable. Any changes to the system involve building and deploying a new version of the server-side application.

All your logic for handling a request runs in a single process, allowing you to use the basic features of your language to divide up the application into classes, functions, and namespaces. With some care, you can run and test the application on a developer’s laptop, and use a deployment pipeline to ensure that changes are properly tested and deployed into production. You can horizontally scale the monolith by running many instances behind a load-balancer.

Issues:

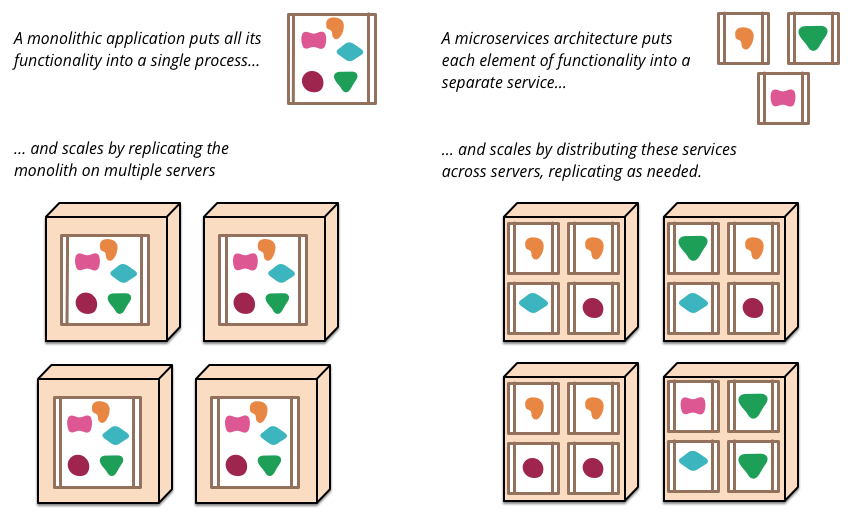

Change cycles are tied together - a change made to a small part of the application, requires the entire monolith to be rebuilt and deployed. Scaling requires scaling of the entire application rather than parts of it that require greater resource.

A pictorial summary:

Characteristics of a Microservice Architecture

Its not the formal definition but the emerged characteristics.

Componentization via Services

To build systems by plugging together components is always desired. But what makes a component. Our definition is that a component is a unit of software that is independently replaceable and upgradeable.

Microservice architectures will use libraries, but their primary way of componentizing their own software is by breaking down into services. We define libraries as components that are linked into a program and called using in-memory function calls, while services are out-of-process components who communicate with a mechanism such as a web service request, or remote procedure call. (This is a different concept to that of a service object in many OO programs .)

Benefits:

- Services are independently deployable.

- More explicit component interface. Most languages do not have a good mechanism for defining an explicit Published Interface. Often it’s only documentation and discipline that prevents clients breaking a component’s encapsulation, leading to overly-tight coupling between components.

Issues:

- Remote calls are more expensive than in-process calls, and thus remote APIs need to be coarser-grained.

Organized around Business Capabilities

When looking to split a large application into parts, often management focuses on the technology layer, leading to UI teams, server-side logic teams, and database teams. When teams are separated along these lines, even simple changes can lead to a cross-team project taking time and budgetary approval. A smart team will optimise around this and plump for the lesser of two evils - just force the logic into whichever application they have access to. Logic everywhere in other words. This is an example of Conway’s Law in action.

Any organization that designs a system (defined broadly) will produce a design whose structure is a copy of the organization’s communication structure.

– Melvyn Conway, 1967

The microservice approach to division is different, splitting up into services organized around business capability. Such services take a broad-stack implementation of software for that business area, including user-interface, persistant storage, and any external collaborations.

How Big is a microservice?

Although microservice has become a popular name for this architectural style, its name does lead to an unfortunate focus on the size of service, and arguments about what constitutes “micro”. In our conversations with microservice practitioners, we see a range of sizes of services. The largest sizes reported follow Amazon’s notion of the Two Pizza Team (i.e. the whole team can be fed by two pizzas), meaning no more than a dozen people. On the smaller size scale we’ve seen setups where a team of half-a-dozen would support half-a-dozen services.

Products not Projects

Most application development efforts that we see use a project model: where the aim is to deliver some piece of software which is then considered to be completed. Microservice prefers the notion that a team should own a product over its full lifetime (As Amazon’s notion of “you build, you run it” where a development team takes full responsibility for the software in production). This brings developers into contact with how their software behaves in production and with their users.

There’s no reason why this same approach can’t be taken with monolithic applications, but the smaller granularity of services is bonus.

Smart endpoints and dumb pipes

When building communication structures between different processes, we’ve seen many products and approaches that stress putting significant smarts into the communication mechanism itself. A good example of this is the Enterprise Service Bus (ESB), where ESB products often include sophisticated facilities for message routing, choreography, transformation, and applying business rules.

The microservice community favours an alternative approach: smart endpoints and dumb pipes. Applications built from microservices aim to be as decoupled and as cohesive as possible - they own their own domain logic and act more as filters in the classical Unix sense - receiving a request, applying logic as appropriate and producing a response. The two protocols used most commonly are HTTP request-response with resource API’s and lightweight messaging.

In a monolith, the components are executing in-process and communication between them is via either method invocation or function call. The biggest issue in changing a monolith into microservices lies in changing the communication pattern. Instead you need to replace the fine-grained communication with a coarser -grained approach.

Decentralized Governance

One of the consequences of centralised governance is the tendency to standardise on single technology platforms. Splitting the monolith’s components out into services we have a choice when building each of them. You can use nay language. You want to swap in a different flavour of database that better suits the read behaviour of one component?

Many languages, many options

The growth of JVM as a platform is just the latest example of mixing languages within a common platform. It’s been common practice to shell-out to a higher level language to take advantage of higher level abstractions for decades. As is dropping down to the metal and writing performance sensitive code in a lower level one. However, many monoliths don’t need this level of performance optimisation nor are DSL’s and higher level abstractions that common (to our dismay). Instead monoliths are usually single language and the tendency is to limit the number of technologies in use.

For the microservice community, overheads are particularly unattractive. That isn’t to say that the community doesn’t value service contracts. Quite the opposite, since there tend to be many more of them. It’s just that they are looking at different ways of managing those contracts.

Microservices and SOA

When we’ve talked about microservices a common question is whether this is just Service Oriented Architecture (SOA) that we saw a decade ago. There is merit to this point, because the microservice style is very similar to what some advocates of SOA have been in favor of. The problem, however, is that SOA means too many different things. This common manifestation of SOA has led some microservice advocates to reject the SOA label entirely, although others consider microservices to be one form of SOA.

Decentralized Data Management

Decentralization of data management presents in a number of different ways. At the most abstract level, it means that the conceptual model of the world will differ between systems. This is a common issue when integrating across a large enterprise, the sales view of a customer will differ from the support view.

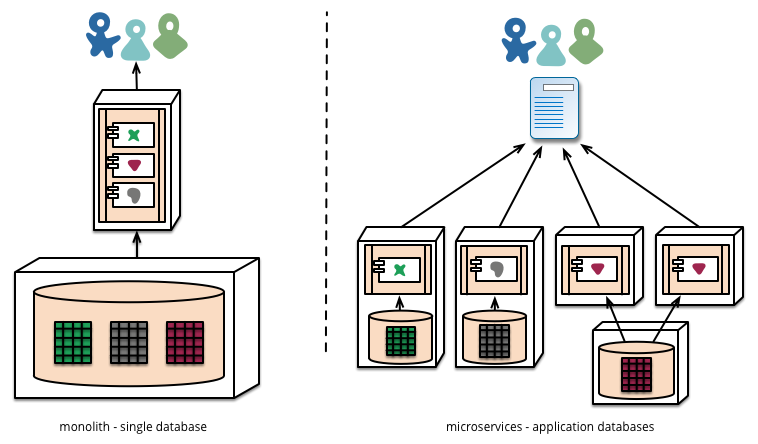

As well as decentralizing decisions about conceptual models, microservices also decentralize data storage decisions. While monolithic applications prefer a single logical database for persistant data, enterprises often prefer a single database across a range of applications - many of these decisions driven through vendor’s commercial models around licensing. Microservices prefer letting each service manage its own database, either different instances of the same database technology, or entirely different database systems - an approach called Polyglot Persistence. You can use polyglot persistence in a monolith, but it appears more frequently with microservices.

Decentralizing responsibility for data across microservices has implications for managing updates. The common approach to dealing with updates has been to use transactions to guarantee consistency when updating multiple resources. This approach is often used within monoliths. Using transactions like this helps with consistency, but imposes significant temporal coupling, which is problematic across multiple services. Distributed transactions are notoriously difficult to implement and and as a consequence microservice architectures emphasize transactionless coordination between services.

Infrastructure Automation

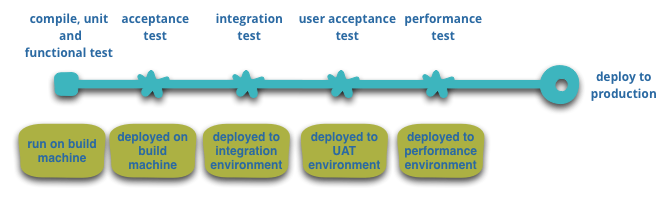

Infrastructure automation techniques have evolved enormously over the last few years - the evolution of the cloud and AWS in particular has reduced the operational complexity of building, deploying and operating microservices. Many of the products or systems being build with microservices are being built by teams with extensive experience of Continuous Delivery and it’s precursor, Continuous Integration.

Design for failure

A consequence of using services as components, is that applications need to be designed so that they can tolerate the failure of services. This is a disadvantage compared to a monolithic design as it introduces additional complexity to handle it. The consequence is that microservice teams constantly reflect on how service failures affect the user experience.

Microservice applications put a lot of emphasis on real-time monitoring of the application, checking both architectural elements (how many requests per second is the database getting) and business relevant metrics (such as how many orders per minute are received).

Synchronous calls considered harmful

Any time you have a number of synchronous calls between services you will encounter the multiplicative effect of downtime. Simply, this is when the downtime of your system becomes the product of the downtimes of the individual components.

Evolutionary Design

Microservice practitioners, usually have come from an evolutionary design background and see service decomposition as a further tool to enable application developers to control changes in their application without slowing down change.

Whenever you try to break a software system into components, you’re faced with the decision of how to divide up the pieces - what are the principles on which we decide to slice up our application? The key property of a component is the notion of independent replacement and upgradeability - which implies we look for points where we can imagine rewriting a component without affecting its collaborators.

With microservices, however, you only need to redeploy the service(s) you modified. This can simplify and speed up the release process. The downside is that you have to worry about changes to one service breaking its consumers. The traditional integration approach is to try to deal with this problem using versioning, but the preference in the microservice world is to only use versioning as a last resort.

Are Microservices the Future?

Those we know about who are in some way pioneering the architectural style include Amazon, Netflix, The Guardian, the UK Government Digital Service, realestate.com.au, Forward and comparethemarket.com.

Often the true consequences of your architectural decisions are only evident several years after you made them.

There are certainly reasons why one might expect microservices to mature poorly. In any effort at componentization, success depends on how well the software fits into components. It’s hard to figure out exactly where the component boundaries should lie. Evolutionary design recognizes the difficulties of getting boundaries right and thus the importance of it being easy to refactor them. But when your components are services with remote communications, then refactoring is much harder than with in-process libraries. Moving code is difficult across service boundaries, any interface changes need to be coordinated between participants, layers of backwards compatibility need to be added, and testing is made more complicated.