Garbage Collection

The Java virtual machine’s heap stores all objects created by a running Java application. Garbage collection is the process of automatically freeing objects that are no longer referenced by the program. Many people think garbage collection collects and discards dead objects. In reality, Java garbage collection is doing the opposite! Live objects are tracked and everything else designated garbage.

Benefits

Garbage collection relieves you from the burden of freeing allocated memory. Knowing when to explicitly free allocated memory can be very tricky. Giving this job to the Java virtual machine has several advantages:

- It can make you more productive.

- A second advantage of garbage collection is that it helps ensure program integrity. Garbage collection is an important part of Java’s security strategy. Java programmers are unable to accidentally (or purposely) crash the Java virtual machine by incorrectly freeing memory.

Overhead

- Managing Overhead: GC adds an overhead that can affect program performance. The Java virtual machine has to keep track of which objects are being referenced by the executing program, and finalize and free unreferenced objects on the fly.

- Unpredictable: This activity will likely require more CPU time than would have been required if the program explicitly freed unnecessary memory. In addition, programmers in a garbage-collected environment have less control over the scheduling of CPU time devoted to freeing objects that are no longer needed.

The graph below models an ideal system that is perfectly scalable with the exception of garbage collection. The red line is an application spending only 1% of the time in garbage collection on a uniprocessor system. This translates to more than a 20% loss in throughput on 32 processor systems. At 10% of the time in garbage collection (not considered an outrageous amount of time in garbage collection in uniprocessor applications) more than 75% of throughput is lost when scaling up to 32 processors.

Why Garbage Collection?

- Limited Memory

- Compacting (De-fragmentation)

The JVM specification does not require any particular garbage collection technique. It doesn’t even require garbage collection at all. But until infinite memory is invented, most Java virtual machine implementations will likely come with garbage-collected heaps.

Let’s start with the heap, which is the area of memory used for dynamic allocation. In most configurations the operating system allocates the heap in advance to be managed by the JVM while the program is running. This has a couple of important ramifications:

- Object creation is faster because global synchronization with the operating system is not needed for every single object.

- When an object is no longer used, the garbage collector reclaims the underlying memory and reuses it for future object allocation. This means there is no explicit deletion and no memory is given back to the operating system.

All objects are allocated on the heap area managed by the JVM.

Garbage Collection Algorithms

Things to do:

- When an object is no longer referenced by the program, the heap space it occupies can be recycled so that the space is made available for subsequent new objects.

- The garbage collector must somehow determine which objects are no longer referenced by the program and make available the heap space occupied by such unreferenced objects.

- In the process of freeing unreferenced objects, the garbage collector must run any finalizers of objects being freed.

The complete algo can be generalised as:

- Defining a set of

roots. - Determining

reachabilityfrom the roots.- An object is reachable if there is some path of references from the roots by which the executing program can access the object.

- The roots are always accessible to the program.

- Any objects that are reachable from the roots are considered

live. - Objects that are not reachable are considered garbage, because they can no longer affect the future course of program execution.

Root

The root set in a JVM is implementation dependent, but would always include:

- Any object references in the local variables and operand stack of any stack frame and any object references in any class variables.

- Any object references, such as strings, in the constant pool of loaded classes. The constant pool of a loaded class may refer to strings stored on the heap, such as the class name, superclass name, superinterface names, field names, field signatures, method names, and method signatures.

- Any object references that were passed to native methods that either haven’t been “released” by the native method. (Depending upon the native method interface, a native method may be able to release references by simply returning, by explicitly invoking a call back that releases passed references, or some combination of both.)

- The Java virtual machine’s runtime data areas that are allocated from the garbage-collected heap. For example, the class data in the method area itself could be placed on the garbage-collected heap in some implementations, allowing the same garbage collection algorithm that frees objects to detect and unload unreferenced classes.

There are four kinds of GC roots in Java:

- Local variables are kept alive by the stack of a thread. This is not a real object virtual reference and thus is not visible. For all intents and purposes, local variables are GC roots.

- Active Java threads are always considered live objects and are therefore GC roots. This is especially important for thread local variables.

- Static variables are referenced by their classes. This fact makes them de facto GC roots. Classes themselves can be garbage-collected, which would remove all referenced static variables. This is of special importance when we use application servers, OSGi containers or class loaders in general. We will discuss the related problems in the Problem Patterns section.

- JNI References are Java objects that the native code has created as part of a JNI call. Objects thus created are treated specially because the JVM does not know if it is being referenced by the native code or not.

The Java virtual machine can be implemented such that the garbage collector knows the difference between a genuine object reference and a primitive type (for example, an int) that appears to be a valid object reference. (One example is an int that, if it were interpreted as a native pointer, would point to an object on the heap.) Some garbage collectors, however, may choose not to distinguish between genuine object references and look-alikes. Such garbage collectors are called conservative because they may not always free every unreferenced object. Sometimes a garbage object will be wrongly considered to be live by a conservative collector, because an object reference look-alike referred to it. Conservative collectors trade off an increase in garbage collection speed for occasionally not freeing some actual garbage.

Approaches to distinguishing b/w live & garbage

1. Reference Counting Collectors

Reference counting garbage collectors distinguish live objects from garbage objects by keeping a count for each object on the heap. The count keeps track of the number of references to that object. > Any object with a reference count of zero can be garbage collected.

The count is changed on following conditions:

- When an object is first created and a reference to it is assigned to a variable, the object’s reference count is set to one.

- When any other variable is assigned a reference to that object, the object’s count is incremented.

- When a reference to an object goes out of scope or is assigned a new value, the object’s count is decremented.

- When an object is garbage collected, any objects that it refers to have their reference counts decremented.

Pros:

- Reference counting collector can run in small chunks of time closely interwoven with the execution of the program. Makes it particularly suitable for real-time environments where the program can’t be interrupted for very long.

Cons:

- Reference counting does not detect cycles: two or more objects that refer to one another. An example of a cycle is a parent object that has a reference to a child object that has a reference back to the parent. These objects will never have a reference count of zero even though they may be unreachable by the roots of the executing program.

- Reference counting is the overhead of incrementing and decrementing the reference count each time.

Because of the disadvantages inherent in the reference counting approach, this technique is currently out of favor.

2. Tracing Collectors

Tracing garbage collectors actually trace out the graph of references starting with the root nodes. Objects that are encountered during the trace are marked in some way. After the trace is complete, unmarked objects are known to be unreachable and can be garbage collected.

The basic tracing algorithm is called mark and sweep.. In the JVM, the sweep phase must include finalization of objects.

Other Type of Collectors:

Garbage collectors of Java virtual machines will likely have a strategy to combat heap fragmentation. Two strategies commonly used by mark and sweep collectors are compacting and copying.

1. Compacting Collectors

Compacting collectors slide live objects over free memory space toward one end of the heap. In the process the other end of the heap becomes one large contiguous free area. All references to the moved objects are updated to refer to the new location.

Updating references to moved objects is sometimes made simpler by adding a level of indirection to object references. Instead of referring directly to objects on the heap, object references refer to a table of object handles. The object handles refer to the actual objects on the heap. While this approach simplifies the job of heap defragmentation, it adds a performance overhead to every object access.

2. Copying Collectors

Copying garbage collectors move all live objects to a new area. As the objects are moved to the new area, they are placed side by side, thus eliminating any free space that may have separated them in the old area. The old area is then known to be all free space.

Objects are copied to the new area on the fly, and forwarding pointers are left in their old locations. The forwarding pointers allow the garbage collector to detect references to objects that have already been moved. The garbage collector can then assign the value of the forwarding pointer to the references so they point to the object’s new location.

Pros:

- Objects can be copied as they are discovered by the traversal from the root nodes. There are no separate mark and sweep phases.

A common copying collector algorithm is called stop and copy. In this scheme, the heap is divided into two regions. Only one of the two regions is used at any time. Objects are allocated from one of the regions until all the space in that region has been exhausted. At that point program execution is stopped and the heap is traversed. Live objects are copied to the other region as they are encountered by the traversal. When the stop and copy procedure is finished, program execution resumes. Memory will be allocated from the new heap region until it too runs out of space. At that point the program will once again be stopped.

Cons:

- All live objects must be copied at every collection. This facet of copying algorithms can be improved upon by taking into account two facts that have been empirically observed in most programs in a variety of languages:

- Most objects created by most programs have very short lives.

- Most programs create some objects that have very long lifetimes.

A major source of inefficiency in simple copying collectors is that they spend much of their time copying the same long-lived objects again and again.

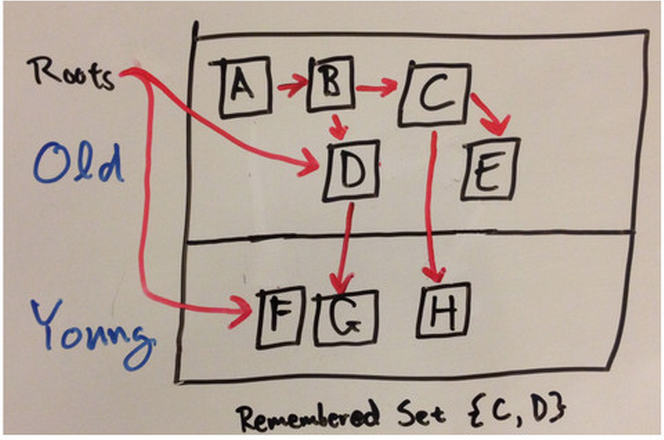

3. Generational Collectors

Generational collectors address stop and copy inefficiency by grouping objects by age and garbage collecting younger objects more often than older objects.

In this approach, the heap is divided into two or more sub-heaps, each of which serves one “generation” of objects.

- The youngest generation is garbage collected most often. As most objects are short-lived, only a small percentage of young objects are likely to survive their first collection.

- Once an object has survived a few garbage collections as a member of the youngest generation, the object is promoted to the next generation: it is moved to another sub-heap.

- Each progressively older generation is garbage collected less often than the next younger generation. As objects “mature” (survive multiple garbage collections) in their current generation, they are moved to the next older generation.

The generational collection technique can be applied to mark and sweep algorithms as well as copying algorithms. In either case, dividing the heap into generations of objects can help improve the efficiency of the basic underlying garbage collection algorithm.

4. Adaptive Collectors

An adaptive garbage collection algorithm takes advantage of the fact that some garbage collection algorithms work better in some situations, while others work better in other situations.

Simple its hybrid which use the specif implementation based on the identified situation

GC Disruption

One of the potential disadvantages of garbage collection compared to the explicit freeing of objects is that garbage collection gives programmers less control over the scheduling of CPU time devoted to reclaiming memory. It is in general impossible to predict exactly when (or even if) a garbage collector will be invoked and how long it will take to run. Because garbage collectors usually stop the entire program while seeking and collecting garbage objects, they can cause arbitrarily long pauses at arbitrary times during the execution of the program. GC pauses can sometimes be long enough to be noticed by users.

If a garbage collection algorithm is capable of generating pauses lengthy enough to be either noticeable to the user or make the program unsuitable for real-time environments, the algorithm is said to be disruptive.

How to reduce disruption: Collect incrementally

An incremental garbage collector is guaranteed (or at least very likely) to require less than a certain maximum amount of time. A common incremental collector is a generational collector, which during most invocations collects only part of the heap.

The Train Algorithm

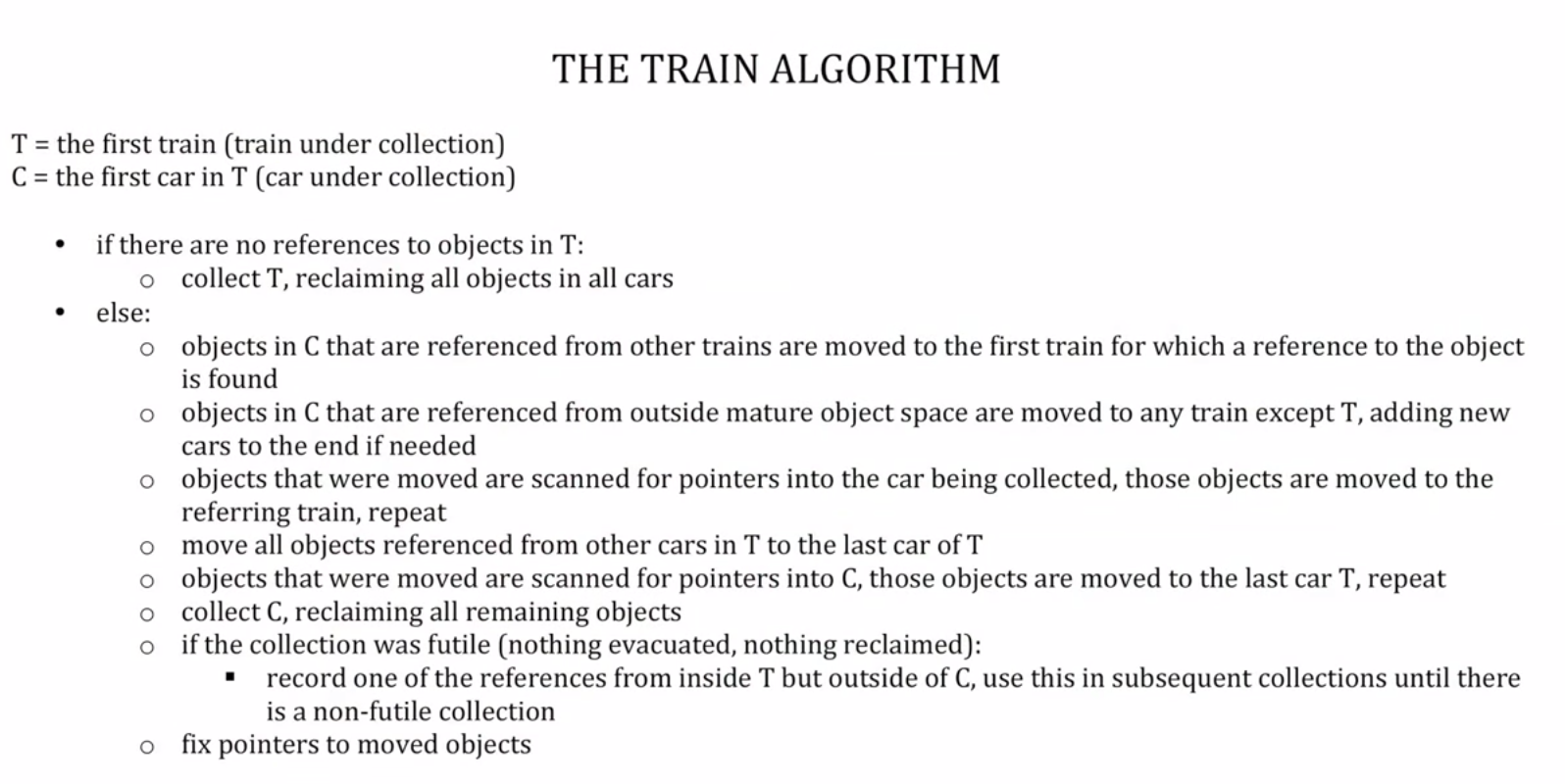

The train algorithm, which was first proposed by Richard Hudson and Eliot Moss and is somewhat currently used by Sun’s Hotspot virtual machine, specifies an organization for the mature object space of a generational collector.

Cars, Trains, and a Railway Station

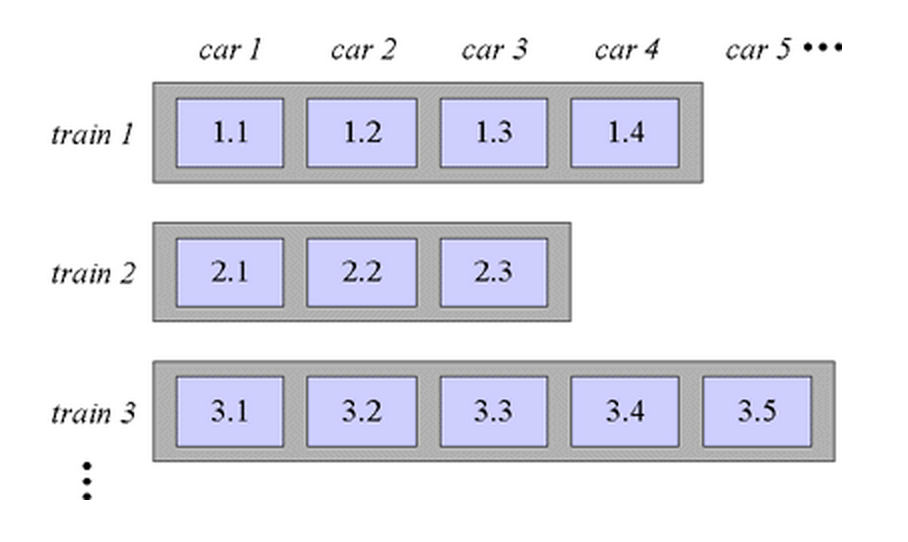

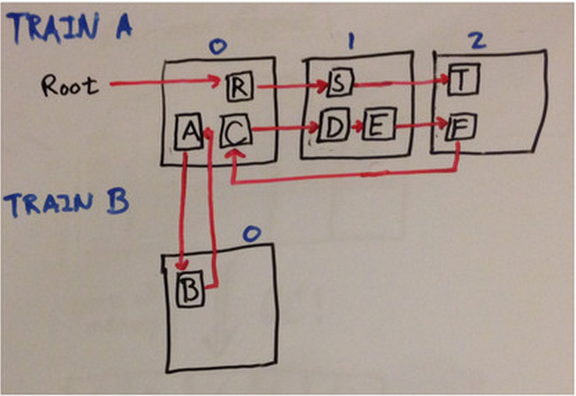

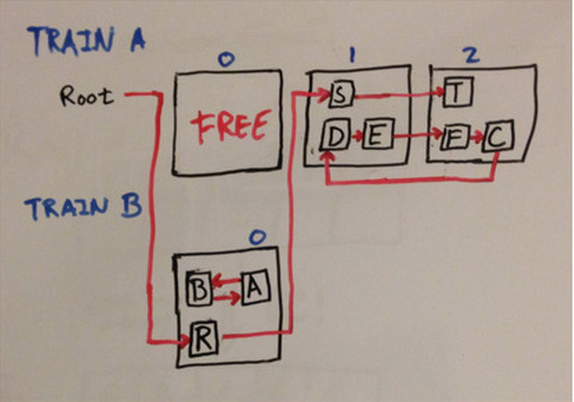

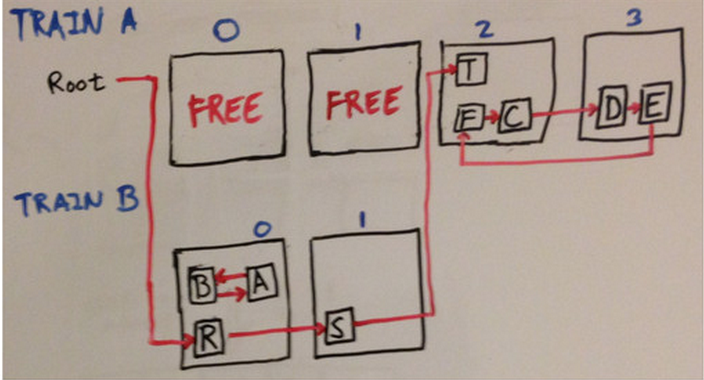

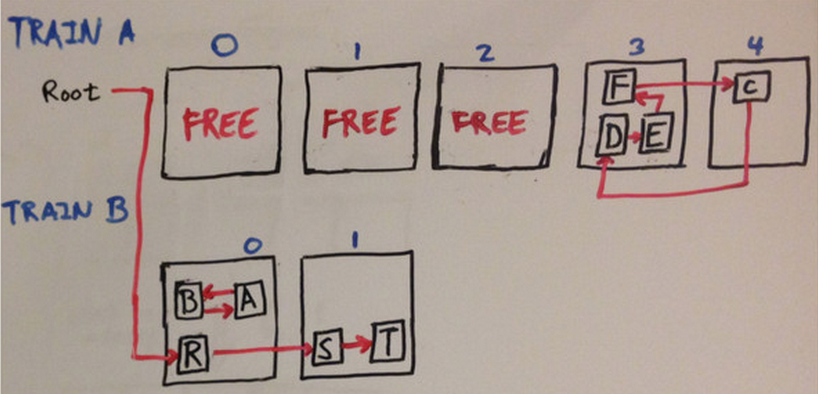

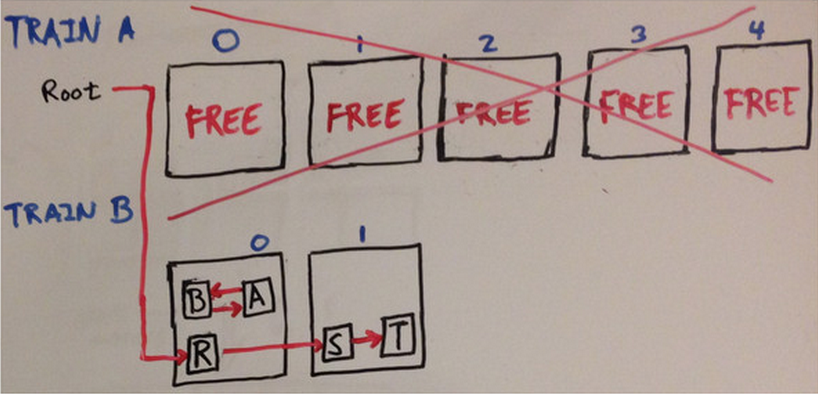

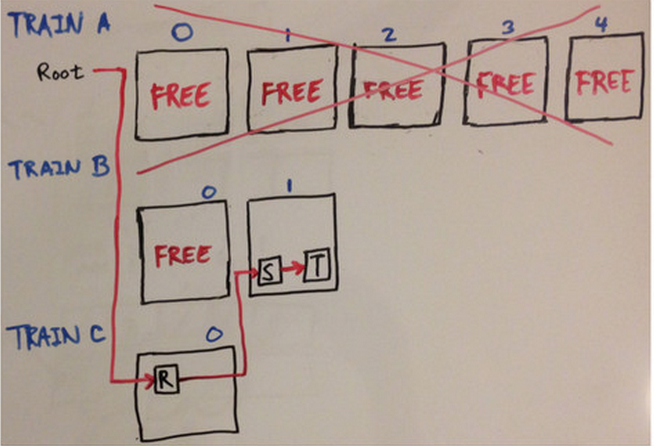

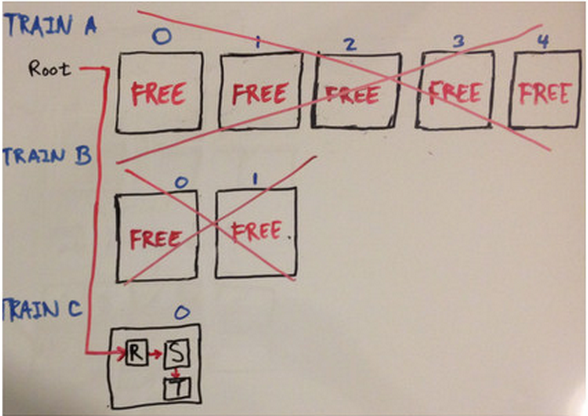

The train algorithm divides the mature object space into fixed-sized blocks of memory, each of which is collected individually during a separate invocation of the algorithm. The name, “train algorithm,” comes from the way the algorithm organizes the blocks. Each block belongs to one set. The blocks within a set are ordered, and the sets themselves are ordered. To help explain the algorithm in their original paper, Hudson and Moss called blocks “cars” and sets “trains.”

In single collection the Train Algorithm collects one Car or one Train.

Ordering: Trains (sets of blocks) are assigned numbers in the order in which they are created. Given this numbering scheme, a smaller train number will always indicate an older train. Within a train, cars (blocks) are added only to the end of the train. This numbering scheme yields an overall order for blocks in the mature object space.

New objects: Whenever objects are promoted into the mature object space from younger generations, they are either added to any existing train except the lowest-numbered train, or one or more new trains are created to hold them.

Collecting Cars

There are three places from which a object in the car C can be referred:

- Outside mature space

- Outside the train T

- Outside the Car C but in train T

Remembered Sets and Popular Objects

The train algorithm can most often ensure that each invocation will require less than some maximum amount of time, but not always because the algorithm must do more than just copy the objects.

Remembered Sets:

- A remembered set is a data structure that contains information about all references that reside outside a car or train but point into that car or train.

- The algorithm maintains one remembered set for each car and each train in the mature object space.

- The remembered set for a particular car, therefore, contains information about the set of references that refer to (or “remember”) the objects in that car.

- An empty remembered set indicates that the objects contained in the car or train are unreferenced (have been “forgotten”) by any objects or variables outside the car or train.

- The remembered set is an implementation technique that helps the train algorithm do its work more efficiently.

- When the train algorithm moves an object to a different car or train, the information in the remembered set helps it efficiently update all references to the moved object so that they correctly refer to the objects new location.

Popular Objects:

- Although the amount of bytes the train algorithm may have to copy during one invocation is limited by the size of a block, the amount of work required to move a popular object, an object that has many references to it, is impossible to limit.

- Each time the algorithm moves an object, it must traverse the remembered set of that object and update each reference to that object so that the reference points to the new location.

- Thus, in certain cases the train algorithm may still be disruptive.

Example

Futile Collections

example ????

Finalization

In Java, an object may have a finalizer: a method that the garbage collector must run on the object prior to freeing the object. The potential existence of finalizers complicates the job of any garbage collector in a Java virtual machine.

Finalization Pseudocode:

- Examine all objects it has discovered to be unreferenced to see if any include a finalize() method.

- Execute finalizers

- Once again detect unreferenced objects starting with the root nodes (call this Pass II). This step is needed because finalizers can “resurrect” unreferenced objects and make them referenced again.

- Free all objects that were found to be unreferenced in both Passes I and II.

If an object with a finalizer becomes unreferenced, and its finalizer is run, the garbage collector must in some way ensure that it never runs the finalizer on that object again. If that object is resurrected by its own finalizer or some other object’s finalizer and later becomes unreferenced again, the garbage collector must treat it as an object that has no finalizer.

More about finalization can be found at How to Handle Java Finalization’s Memory-Retention Issues - See more at: http://www.devx.com/Java/Article/30192#sthash.fLBHOsXe.dpuf.

The Reachability Lifecycle of Objects

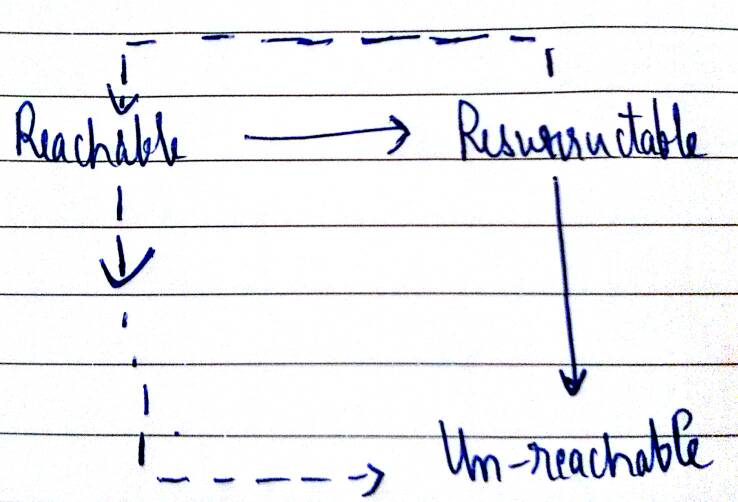

In versions prior to 1.2, every object on the heap is in one of three states from the perspective of the garbage collector: reachable, resurrectable, or unreachable.

There can be two possible flows in between these states:

In version 1.2, the three original reachability states – reachable, resurrectable, and unreachable – were augmented by three new states: softly, weakly, and phantom reachable. Because these three new states represent three new (progressively weaker) kinds of reachability, the state known simply as “reachable” in versions prior to 1.2 is called “strongly reachable” starting with 1.2.

References:

- Garbage Collection - Inside the Java Virtual Machine - Artima

- Andrew Turley on Incremental Mature Garbage Collection Using the Train Algorithm

- dynatrace - memory Management

- How to Handle Java Finalization’s Memory-Retention Issues - See more at: http://www.devx.com/Java/Article/30192#sthash.fLBHOsXe.dpuf.